It was a pleasant day, long before the pandemic. I was inside the Gloworld at the Ikeja City Mall to fix something with my phone line. Everything was going well until the sound of gunshots – skrrrahh, pap, pap, ka-ka-ka-ka-ka! I jumped to my feet very quickly and scanned the environment to determine the safest escape route. I quickly considered that if there was to be a stampede everyone would make for the only door to the small room, and run towards the direction the salvos were coming from. So I decided that the small room behind the service agents, where they usually kept their stock of phones and accessories would be the safest place to hide.

People were getting increasingly agitated and asking the lone security guard what the problem was. The sounds went off again, this time louder and longer, and in the ensuing pandemonium I made my move. It was from the safety of the storeroom, while praying feverishly that I heard people explain what had just happened – and then they all burst into laughter as I emerged from my fortress. They were laughing at me! One lady gathered herself and said, “Oga, na balloon, no be bullet”. A nearby store that sold balloons and other celebratory materials simply had an incident with some of their balloons popping off. Indeed, it was balloons and not bullets. So, I had the walk of shame, with stares from staff and customers alike, not back to my seat, but out of the store and headed home. I was thoroughly embarrassed.

As I drove home, I thought hard about what just happened. I knew exactly where it came from. On Wednesday, March 13, 2013, I was returning from a trip with my colleague. Our wives had driven to the airport separately to pick us up. As we approached the car park Tina and I said our goodbyes to Tolu and Bolanle as we went in different directions to find our vehicles. Tina decided to treat me to suya because she knew I longed to reunite my taste buds with Nigerian food. So, she described where she parked the car and handed the keys to me so she could buy the delicacy. Her kind gesture is what saved her from the traumatic experience that was to follow.

As I pushed the trolley along within the large car park, I heard gunshots go off from very close quarters. I was caught up in a robbery in progress. About ten dare devil robbers had stormed the Murtala Muhammed International airport, reportedly in trail of a huge sum of dollars that had been transported in a bullion van enroute Dubai. It was a brazen case of attempted “relooting” as the thieves made to take their share of the illicit financial flows, resulting in the death of two policemen and one of the robbers in the gunfight that followed.

It was a very horrible experience. At a point, I saw one man in a flowing gown drop flat to the ground and roll under a car to hide. I tried to follow him, but it wasn’t easy – many are called but few are slim enough. He kicked and yelled that I should find another hiding place. As I ran, another volley of gunshots went off which made me scrape my knees on the concrete resulting in a painful injury. By God’s grace I was able to escape the theatre of violence and reunite with Tina. We went home in a taxi that night, too traumatised to return to the carpark to find the car.

In the years before that incident I had led missions to five post-conflict countries to engage with young people rebuilding their lives. Our audience included victims of the most horrendous war crimes as well as former child soldiers. I had heard war stories and prided myself in being able to relate with them during counselling. My later experience, which is nothing compared to theirs, showed me how wrong I was, and how it takes a lot more effort to truly empathise with people especially when you haven’t shared in their experiences. I have since come to learn more about empathy and how this is a crucial factor in conversations about leadership and development in Africa.

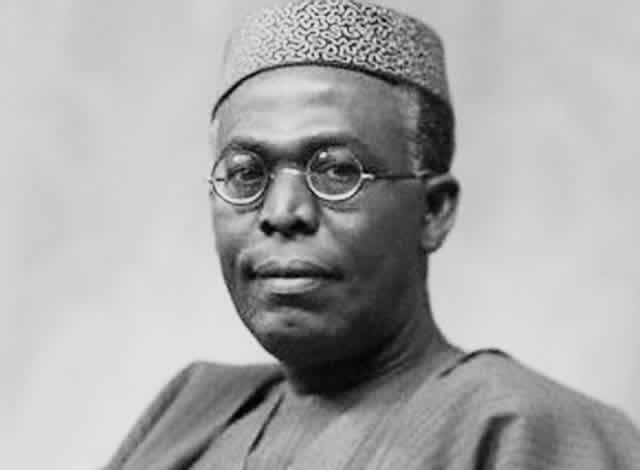

The late sage Obafemi Awolowo wrote a lot about the subject of love, empathy, and mental magnitude. He was born into a peasant family and his prospects in life were further dimmed when his father died while he was still very young. Asides the existential struggle for food, clothing, and shelter, he faced the challenge of continuing his education. This experience accounts for his dogged commitment to free and universal education, and his belief that education is the fundamental building block for development in any society. The trials of an indigent boy resulted in empathy, which in turn led to enduring political ideologies and structures that posited a relationship between education, political consciousness, and development. His achievements in mass education and development as the premier of the defunct Western Region remains unrivalled in the history of post-colonial African states.

On love, Awolowo saw love as an important virtue for anyone aspiring to lead, which is in sharp contrast to the chicanery, knavery, and brutish credentials required in Nigerian politics these days. Aboluwodi stated that “Awolowo saw accountability, transparency and the like as the mainstream of political order which may constitute the thesis while selfishness, greed and so on constitute a negation of this order. The conflict between man’s natural instincts like greed and impulse is resolved when these greedy and selfish acts are overcome and love which manifests in social justice, fairness and equity is attained. Love then becomes a quality that the state or family must aspire to have. Just like the state aspires to reach its perfection when it has freedom, morality and rationality in Hegelian dialectic, Awolowo’s perfect state is achieved when the state and its parts attain a perfect state of love. Love becomes the quintessence of state and human interaction.”

On mental magnitude, Awolowo theorised that those who aspire to lead should be able to bring their acquisitive tendencies under the control of reason, and cultivate self-discipline. He further postulated that good leaders should abhor vile emotions and vices including anger, fear, malice, gluttony, drunkenness, and sexual immorality. He believed that only those whose interests are subsumed under the interests of the people can succeed as leaders. Achieving this state of consciousness is what Awolowo called the regime of mental magnitude – the ability to subvert human proclivities for crass materialism and indulgences in favour of self-discipline and rational behaviour.

With very few exceptions, Africa has since retreated from producing leaders with the virtues of love, empathy, and mental magnitude that Awolowo wrote about. Our human development indices have declined steadily over the years because of the many reprobates in power stifling the good efforts of the few honourable people who manage to get to positions of authority. That is not to say we haven’t had leaders who had no shoes while they were growing up. We once had the case of a minister who was in tears during inspection of dilapidated critical infrastructure, but ended up becoming one of the most prolific looters of public funds. It has simply been a case of misplaced empathy.

Paul Ekman distinguishes between different forms of empathy. He wrote about “cognitive empathy,” which is the ability to know how the other person feels and how they think. While it has its good aspects, this sort of empathy has been associated with the “dark triad” – Narcissists, Machiavellians, and Sociopaths, who possess this attribute while having no sympathy for their victims. A torturer needs this ability, if only to better calibrate his cruelty – and talented political operatives no doubt have this ability in abundance. (Goleman, 2007).

Majority of the current crop of political leaders understand the politics of poverty all too well. They are skilled in the art of exploiting the desperation of poor Nigerians, who are in the majority, to advance their own selfish interests. Add to that wizardry in identity politics and you have tales of heists by uncommon people in power who go against the will of God by stealing funds meant for development, while people from the regions they claim to represent wallow in poverty. “Compassionate empathy”, on the other hand, according to Ekman, helps people understand another person’s predicament and not only feel with them, but are moved to do the right thing and help them. Some statements by serving public officials give them away that they are far removed from the pains and suffering of the people.

In the months and years ahead, when we have another chance to elect leaders to different positions of power, Nigerians would do well to pay greater attention to the personal lives, characters, and antecedents of those aspiring to office – because desperation and a lack of moral rectitude in aspiring leaders, according to the great Awo, is a veritable hint of disasters waiting to happen. We have recycled deceptive populists, mercantilist demagogues, and indignant godsons of entitled godfathers, over many years with little to show for it. This is the time to revisit existing models of leadership recruitment, and find good people in unlikely places to lead us. Moral exemplars who have been the bulwark against the free fall of society. Empathetic men and women amongst us that we often remark would make good leaders but are not cut out for the politics of money and violence. These are the exact corps of patriots we need to salvage our country.