Unknown to many foreigners, Canada, a great and influential country, has about 50 ethnic minority groups, otherwise known as Red Indians. These indigenous or aboriginal people were the original inhabitants of the land before the arrival of Europeans. According to the 2016 Canadian census, more than 1.6 million people in Canada are Aborigines. They constitute 4.9 per cent of Canadian population. Southwest Bureau Chief BISI OLADELE, who has just returned from Canada, reports.

There are no fewer than 630 first nation communities in Canada, which represent more than 50 nations and 50 indigenous languages.

The peoples include Inuit, Metis and Oujé-Bougoumou Cree. Interestingly, the minority groups, who speak English or French, being the official languages of the country, enjoy greater privileges to develop their languages, arts, culture and values along with those of the Whites who are the most popular. Called First Nations, they have specialised institutions preserving their cultures with First Nations University as the ivory tower offering courses on their cultures, languages, arts, religion and values, among others.

I took a 300-Level course entitled: Contemporary English Usage in my days at the Obafemi Awolowo University. I vividly remember how my lecturer, then Dr Olowe, explained with glee, how many Americans (then Britons) moved upwards to found the country known as Canada today because they did not agree with the approach of rejecting anything that bore semblance with the British culture while fighting hard to gain independence from the Great Britain around 1774. Olowe did not dig deep into the fact that the Britons (who were Americans already) conquered the inhabitants of the land of Canada and lorded their language and culture on them as they took complete control because we were only looking at the reason behind the difference in the spelling, lexicons, slangs etc between American and British English. The idea was to equip us with the history of modern English so we could have a better understanding of the contemporary use of the language in which we were to be awarded a honours degree.

Three years later, I stumbled on George Guest’s book entitled: The History of Modern Civilisation. Guest did a thorough job, explaining the emergence of the US, then regarded as the New World. It was in the book I read much more about the original inhabitants of the land of America and Canada. But Guest and Olowe only called them Red Indians.

Since then, I was imagining how the inhabitants (or owners) of the land of world’s greatest nations look like. Do they look like the Asian Indians? Are they white, black or Caucasian? All these questions never received an answer until I travelled to Canada for the first time in July.

My host, who is a family friend, teaches Philosophy at the University of Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada. He was conducting me through the beautiful university campus on my first day of visit when he led me to a beautiful building that stood alone from others. Then he declared: “This place is First Nations University. It is like a part of U of R (University of Regina). Their students are also our students. Here, they study about the original inhabitants of the land of Canada. They …”

I cut in: “You mean the the Red Indians are recognised here?” I asked, curiously. He answered in the affirmative. I was so elated as if I just won a lottery as I immediately concluded in my mind that I finally got the opportunity to meet the Red Indians at the long last.

“Are they here?” I asked.

“Yes. Students study their culture, language, arts, values etc here in this university.

“Are they the lecturers here?” I asked again. “Yes.” He answered. Then my interest grew bigger.

My friend further told me that most of their staff members are indigenous people. “It’s just their university.” He said, smiling as he recognized that he was satisfying my curiosity. My friend relished the fact that a Nigerian was giving a fellow citizen the much information about his new country to the level of great satisfaction. Before Canada, I had visited the US severally without ever sighting a Red Indian, the country in which their history is most popular.

With this discovery, I stepped out of the building, caught a better glimpse of the building and soaked in its architectural beauty. Then, I walked in again and prepared myself for an adventure. As we paced forward, we saw a young lady who was the receptionist. We also saw a few people descending the stairs and walking out of the building. I asked my friends quietly if they were the people I was eager to meet and he answered in the affirmative. “Wao! So, this is how Red Indians look like.” I told myself, Savouring my new knowledge.

In that ecstasy, I stepped forward to interact with the receptionist. She was warm and polite, as expected. I told her that I was a visitor from Africa, and that I was interested about the university and First Nations, as indigenous peoples were officially called in Canada. She took time to give me some printed materials about the subjects and also gave me descriptions of how I could move round the various public compartments of the building.

Eventually, I succeeded in booking an appointment with the institution’s Vice President (Academic), Bob Kayseas, for an interview about First Nations. Every bit of the interview exposed me to the history of the country. The interview also gave much knowledge about First Nations, their history, religion, language and values.

Who are First Nations?

Canada has a number of categories of indigenous peoples as entrenched in the constitution. They are First Nations. There are the Metis, Cornimores (used to be called Eskimos). They changed that appellation because they did not like it. We were also called Red Indians for generations but we did not like it though people still call us Indians. We did not like that name simply because of the origin. It was Christopher Columbus that originated it. He called the people he saw on landing on American land Indians. From there, people started using that name derogatorily for us. Yet, a lot of them in the United States still refer to them as Red Indians. Up north Canada, we have the communities of indigenous peoples including the Lakrons. There are really lots of indigenous peoples in Canada. So, describing First Nations, we are the Indians or indigenous peoples in Canada. I am National Abbey, a large category of Indians to the east coast of Canada down to Washington DC and Saskatchewan. We were the original inhabitants of this land (Canada) and we actually exist all across North and South America (Chile, Peru and Argentina). We don’t know what the population was before the first contact (with Europeans) but there are a lot of indigenous peoples across the vast land of America. For us in my original community, my people came from Eastern Canada. We did not get to Saskatchewan until late 1800. As at the time my chiefs and the leaders signed treaty, my people were still moving.

In Saskatchewan here we have five primary groups of indigenous peoples. We have the Dene who are up in the north; we have the Tsuu who spread into the United States; the Cree, the Soto and the Kluane.

Indigenous people have been around for a long time with many challenges confronting them since after the first contact. They participated in the economy greatly. But, the worldview of the Europeans is quite different from that of indigenous people. They did not actually respect indigenous sovereignty. Europeans viewed this land as empty, thinking it was a land they could conquer because it was not inhabited. But we were here. And that translates into many different challenges. For instance, they tried to get rid of Indians in all ways; they wanted us to just be like them. They tried to get rid of our languages and cultures. We have fought up to 500 years in that process. In my community today, there are lot of people who still use our language and stick to our culture. So, it’s a long process to maintain our indigenous world view, language and culture. They are still in many ways challenged. We still have many struggles.

There are over one million people categorized as indigenous people. About 600,000 of those people are First Nations like me. We have the Metis who are about 200,000 people who have both indigenous and European ancestry. Some have French or Scottish ancestry. The Inuit are small group of people. The Inuit have their own territory – Nunovit. It’s up north.

Historically, do First Nations trace their origin to anywhere outside Canada or North America as a continent?

No. All of us trace our origin to this land. There are arguments or suggestions for example that we came from the Eastern continent (Asia). That was a challenge some 15,000 years ago because, like I said, we have South American brothers and sisters who had early civilisation and cities as at first contact.

Are there similarities between the cultures of indigenous peoples of Canada and any other one outside North America?

I have always seen more areas that are not similar. For instance, there are words in our language which convey certain meaning if you do something bad to a rock. It shows that we are part of nature. We believe that water and rock has spirit. When we take the spirit of an animal, we make sacrifice to offer thanks for giving us sustenance. We have a relationship with the world around us. There is a community among indigenous people who believe that pipestone was created after a large flood like that of the Bible during Noah’s generation. It is believed that the pipestone is a remnant of that great flood. So, we reverence it.

Our world view is very different. We believe that the community and the people come first. I have responsibility to my family, to my community. So, when we make money, we take care of family, including grandchildren, my wife’s family etc first and then we take care of the community. We are communal in our culture. We keep extended families – grandparents and grandchildren as well as in-laws live in the same house. The man takes care of them all. We take care of one another as much as we can. We don’t have nuclear family type per se.

With our money, we don’t have that saving mentality that European culture has which to us in many ways has been detrimental. But it’s probably a good idea to save for the future. But Europeans don’t understand that about us. When a First Nation man receives his pay and does not show up the second day, they conclude that we are lazy not knowing that he is doing what the culture prescribes which is to take care of his family and community with his income. The man believes he already has all he needs to take care of his family and community today. He believes that there will be supplies for tomorrow. That’s our people’s belief. We believe we can go to the lake and fish to eat tomorrow. But the Europeans believe that we need to store food and other things because of tomorrow but that is not our own culture. Because of that difference they just call us lazy people. They believe we enjoy life only for today without thinking of tomorrow. But that’s not so. Our worldviews are just different.

In your history, were there times you had contact with Africans?

I don’t know. But, I know we have a word in our own language for an African person. Some of the words in our language arose through our contact with other people in the world. For instance, we call watch a little sun because we calculate time by the sun.

That’s a similarity with African culture because our forebears also used the sun to calculate time.

Yes, ours did too.

What aspect of your culture is most important to you as a people?

It’s our language. A language expresses everything about a people. In my language, for instance, wealth means living a good life. My language tells me that I should make a living in a good way, care for my family, honour nature. My language expresses this belief as a different concept from that of the Western culture. So, language is the most important because it expresses my relationship with my family, nature, to anybody around me and my role in this world. It’s an expression of our worldview. My parents spoke no other language at home apart from ours. But I speak a lot of English because of my schooling. So, every time I go back home they make fun of me when I try to speak our language.

A few years ago an organisation wanted to employ more indigenous workers so they could understand their world view the more. The project was in Saskatchewan. The guys were paid and they did not come back the following week. It took a couple of months for them to find out that the real reason they did not come back was because they had to go back to their communities to prepare for winter. They were hunting as at the time they were engaged. As soon as they were paid, they needed to go back and connect with their families to prepare for the winter that was already knocking on the door. They were not lazy; that is just the culture. That helped the researchers to understand the culture better. They have the responsibility to make a living in a good way. They also have the responsibility for the well-being of their families and their communities, not just taking care of themselves alone. So, they went back home to prepare their families and communities for winter.

How developed is your language in Canada?

My own language is one of the most preserved indigenous languages (Ojibway). It is spoken by many groups. The language has many dialects. Ojibway speakers will be about 600,000 people. There are over 50 indigenous languages in Canada. Other languages include Cree, Dene and Micmac.

Is any of the languages studied in school?

No. We have pushed and pushed for their study in schools because the two official languages in Canada are English and French. For many years, the Federal Government makes it illegal for us to practise our culture. They took over 100,000 children of indigenous people and put them in residential schools to ensure that they don’t speak indigenous languages. They want them to speak only English or French in the east. But we have also been creating our own. We have places with many of our kindergarten where they are exposed to the Cree language so they can develop a good foundation. We, in First Nations University, have a programme up north called Dene Teacher Education programme. It’s a post-secondary education programme for future teachers. Many of the courses are in Dene. That’s growing more and more across the country. There is more participation and cooperation from the government side now. That’s the only way to preserve our language because we were challenged for very many years in the past.

Now that many of your youths are moving from your communities to cities where they use only English or French, don’t you think that will be a challenge to the preservation of indigenous languages?

We are also trying to integrate our languages in riverine areas more and more. For instance, we have a school here in Regina where students are allowed to take Cree. We want to have Aborigine programmes in urban areas. This is one of the ways to integrate our languages. People come to First Nations and take all kinds of languages. There has got to be education to maintain our languages. We are creating a Dene Master’s programme to enable us teach communities how to preserve languages. For instance the Canadian government is creating the Indigenous Language legislation. Consultations are going on over it. It’s all about preservation of our indigenous languages. Whereas it was about eradicating indigenous languages but the government is supporting their preservation now. The government just approved a $30 million school for my community. The construction is going on right now.

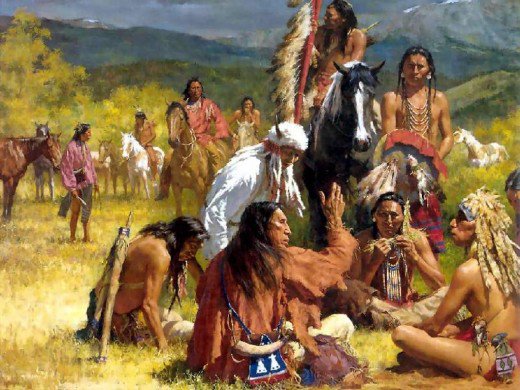

How do First Nations traditional attires look like?

Our dressing culture is now fully European. We have a festival called pow-ow. Very few people wear our traditional attire now. They only wear it during ceremonies. We don’t really have many traditional attires. Time has overtaken those attires.

Do First Nations still celebrate festivals? If they do, what are they?

Yes. Pow-ow is a good example where the community people come together to celebrate the pow-ow dance. We also have the rain dance. It’s a four-day long event during which we fast. It’s about honouring our lives, nature and recognition of what we have and showing appreciation for life and sacrifice for all we have.

What’s the religious belief of First Nations?

We have a strong connection with the Creator. We believe that there was an entity that created everything. He made us part of everything. We make reference to animals as brothers and sisters. In my language, there is a word expressing that something is going to come back at me if I do wrong to animals.

In First Nations, do you believe that there is a supreme being who created all that we can see?

Yes.

How do you relate with that Supreme Being in your religion?

In English, He is called the Creator. In my language, He is called the Manitou. The Manitou, we believe, is the creator of everything we see through which we make a living. So, we have the laws that the creator gave us to help us live our lives. These help us forgive one another, support one another. They help us live life in a good way, respect all nature. In my home we still pray almost every other day. There is a sweat lodge where we say prayers. As you light the sweet grass and the smoke goes up, we believe the smoke carries your prayers up. We use sweet gas to do that. Sweat lodge is like the worship centre just like a church.

How often do you pray to the Manitou?

Probably, it is every day. For instance my grandchildren in my home pray regularly for good dreams. So, they pray in the evenings. My wife prays in the morning before we leave for work.

Culled from The Nation