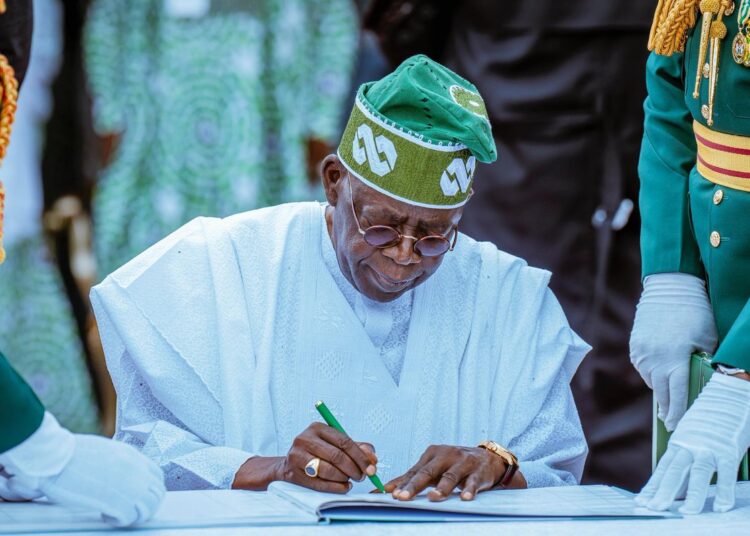

While delivering a sermon at a Ramadan Tafsir in the Presidential Villa on Wednesday, February 18, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu rallied Nigerians to embrace the virtues of unity, peace, and moral renewal. He also asked the people to forgive his wrongdoings. Not many Nigerians picked up the essence of the president’s plea for forgiveness, but when news broke on Thursday that the Federal Government was just about to commence the release of capital votes for 2024 and 2025 budgets, I got the president’s drift.

As a democrat, President Tinubu must have reasoned that failure to implement the capital components of a nation’s budget amounts to a letdown of the people and that he would have to apologise for his administration’s failure to deliver democratic dividends through the 2024 and 2025 budgets. According to reports emanating from the National Assembly, the Federal Government would release 30 per cent of the capital votes of the 2025 budget between now and March 2026, while the remaining 70 per cent of the capital votes would be rolled over into the 2026 budget.

Minister of State for Finance, Dr. Doris Uzoka-Anite, who confirmed the readiness of the administration to pay the capital components of the 2024 and 2025 budgets at the Senate on Thursday, said that the Ministries, Departments, and Agencies (MDAs) have been directed to upload their cash plans to facilitate disbursement for 2025 projects. “The financial management system is back online. We are ready to start, but MDAs must complete their documentation requirements,” she stated. What the minister said in simple terms was that the administration has not been able to fund capital projects, which are usually categorised as dividends of democracy in the 2024 and 2025 budgets, and that payment of 30 percent of such projects would soon commence. Now you know why government contractors staged a protest a while ago within the precincts of the National Assembly, and you also know why President Tinubu is seeking forgiveness.

Budgets and budgetary processes have been more of voodoo economic activities, at least since the return of democratic rule in 1999. In 2004, I was in a conversation with the then Chairman of the Senate Committee on Appropriations, Senator John Azuta Mbata. I asked him what the essence deficit budget was and why it was possible for a country to spend the money it doesn’t have. He told me in a few words, “Adisa, this document, you won’t understand.” I was later to know that the nation’s budget is full of the more you look, the less you see. Budget presentation is a ritual, and it’s difficult to know whether the gods receive the offerings. Ordinarily, a budget encapsulates the estimates of the government’s income and expenditure for the forthcoming year, largely grouped into two blocs, recurrent, and capital votes. The recurrent votes encompass the government’s running costs, emoluments, and contingencies, while the capital votes include funds set aside for execution of projects in the various sectors of governmental endeavour, health, education, road infrastructure, and so on.

Since the restart of democratic rule in 1999, recurrent expenditure has always taken the lion’s share of government projections. Mostly standing at 70-30 per cent. So, most of the time, when governments celebrate a 70 per cent budget performance, it is the execution of recurrent votes. But that’s more like running a government for the civil servants, by the politicians, and for the technocrats, because there is nothing in the recurrent votes to take care of the dividends of democracy for the people. Maybe we should credit President Tinubu for refusing the allure of celebrating the claim that his budgets have performed some 68-70 per cent mark in 2024 and 2025. Maybe we should thank him for being truthful enough with the fact that the funds meant to activate the dividends of democracy, including the legislator’s constituency projects, have been held in abeyance all along.

Having failed to secure an answer to the nagging budget question since 1999, I was somewhat hopeful that the coming of the acclaimed progressives into government in 2015 would change the face of budgeting in Nigeria, especially with the President Muhammadu Buhari Change mantra. I knew that Buhari knew next to nothing about the economy, but was hopeful that the eggheads in his party, who have energetically criticized the government of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) since 1999, would do things differently. In 2015, as President Goodluck Jonathan was exiting, Nigeria’s budget was N4.5 trillion, and in the entire five years of his administration, the budget was N25.296 trillion (about $156.569 billion). When Buhari mounted the saddle, the claim was that the size of the budget should be bigger, and the 2016 budget climbed to N6.061 trillion, while the total budget under the Buhari years from 2015 to 2023 stood at N97.018 trillion (about $228.641 billion). You would sensibly think that the increment in the size of the budget would tend towards the productive side, but alas, the very first budget of the Buhari years was more of the cut-and-paste of what we had in the years past. In the Tinubu years thus far, nothing has changed in the budget line. It is still the envelope system, with perpetual incremental votes. This means that while an agency got N10 million for the purchase of computers and accessories in the Jonathan years with a N4.5 trillion budget, the same agency would get N5 billion for the same purpose in the N58 trillion budget of Tinubu. Remember that value addition is not guaranteed. The problem with the cut and paste envelope system of budgeting here is that budget subheads are not tailor-made to the needs of the people, and with 70 per cent already allotted to recurrent expenditure, the envelope on that side keeps getting fatter. The capital votes had continued to suffer, even as they grew leaner.

So, from way back in 2016, I have remained shocked that despite the many years of criticisms heaped on the PDP for bad governance, the egg heads in the progressives camp would not query the budget lines that kept repeating itself with no tangible impact on the people. For instance, the magicians in the MDAs already know how much they would need to service generators from January to December, how many times power would be available, such that they account for the accurate number of litres of fuel needed to run the offices and how many times the generators would be serviced due to the length of use. Those figures are never short because they always record 100 per cent performance at the end of each year. Technocrats also must keep buying new copies of computers every year, and they know the amount of software they would need to replace from January to December. They have foreign and local tours, which also keep ballooning in figures as the budget size increases. The essence of my take is that despite the enormous size of redundancies in the national budget, the Federal Government and the National Assembly kept repeating the hollow ritual each year.

One is shocked that the huge redundancies that are packaged as recurrent budgets don’t get scrutinised despite the change of hands at the presidency. At the end of each year, you see civil servants hosting workshops they don’t need, even as some officers keep vigil in their places of work just to tidy the books between late November and December. Unfortunately, such vigils have nothing to do with democracy dividends the people desperately need. The 30 per cent of capital votes from the inception of this Republic have often come from external borrowing. So, when the lenders fail to shake body, the projects suffer repeated carryovers. That is why you will see a project like the Lagos-Ibadan Expressway remain under construction for nearly two decades. The Ibadan-Oyo-Ogbomoso-Ilorin Expressway has been under construction since 2001. There are many such projects littered across the country as they suffer years of delay and apparent neglect. Even the recently opened Akwanga-Makurdi Expressway, which has been tolled, is yet to be completed. Because the money for capital votes is largely from external borrowings, there was no surprise that the N25.296 trillion budgets of the Jonathan years made little impact on the nation’s infrastructure in those years. The Buhari era budget, which stood at N97.018 trillion, in fact, made near zero impact on the infrastructure sector.

I do not know why the Tinubu government has been unable to fund capital budgets since 2024, despite the celebrated impact of fuel subsidy removal on government finance and the praises from the IMF/World Bank.

Whatever the excuse, we have to acknowledge the president’s plea for forgiveness as a mark of repentance. It should also signpost the beginning of proper scrutiny for the often ballooned and irrelevant components packaged in the annual recurrent budget. For instance, why should every office buy new computers annually, the security agencies and the Federal Road Safety Corps procure hundreds of vehicles on an annual basis, but there are no strict audits of the whereabouts of these vehicles. Why should public servants keep junketing around the world in the name of foreign training and tours, in an era where the government cannot raise funds to fix roads? There are so many whys in the budget document that should seize the attention of an accountant like Tinubu. As the funding of the capital components of the budget resumes in arrears, let the government ensure that this is the last time a tokenistic vote is allotted to capital components of the budget. There is nothing that says that the capital and the recurrent votes cannot stand at 50 per cent apiece.

(Published by the Sunday Tribune, February 22, 2026)