Nigeria’s 2026 tax reform arrived with both promise and pressure. After years of overreliance on oil revenue, shrinking fiscal space, and rising public debt, the state’s resolve to strengthen non-oil revenue is understandable. A modern economy cannot function without an effective tax system. On paper, therefore, the new tax regime represents a necessary step toward fiscal sustainability.

Yet taxation is not only about numbers. It is also about legitimacy, trust, and social consent. This is where the early implementation of the new regime has raised troubling signals that deserve sober national reflection.

At its core, the reform seeks to consolidate Nigeria’s fragmented tax laws, modernise administration through digital tools, and broaden the tax base. These objectives are sound. Nigeria’s tax-to-GDP ratio remains among the lowest in Africa, and inefficiency has long plagued revenue collection. Any serious government must confront this reality.

However, good intentions alone do not guarantee good outcomes. The problem confronting the 2026 tax regime is not its philosophical justification, but the manner of its rollout and the context in which it operates.

First, there is the issue of public anxiety. Since January 2026, fear has enveloped large sections of the population — not because Nigerians oppose taxation, but because the reforms coincided with a period of severe economic strain. Inflation remains high, purchasing power is weak, and households are still adjusting to subsidy removals and currency volatility. In such an environment, any new or more aggressively enforced tax measure is easily perceived as punitive, even when it is not intended to be so.

Second, communication has been inadequate. Tax laws are complex by nature, but complexity becomes dangerous when paired with opacity. Many citizens and small businesses remain uncertain about what has changed, what applies to them, and what protections exist against arbitrary enforcement. Where clarity is absent, rumours thrive. Fear, once entrenched, undermines voluntary compliance — the very foundation of a successful tax system.

Third, and perhaps most damaging, is the persistence of multiple taxation. While federal authorities speak of consolidation, businesses on the ground continue to face overlapping demands from federal, state, and local governments. Levies with different names but similar purposes are imposed concurrently.

For small and medium-sized enterprises, this is not merely inconvenient; it is existential. Compliance costs pile up, margins shrink, and informality becomes a survival strategy. A tax reform that does not decisively resolve this problem risks being judged a failure regardless of its elegance on paper.

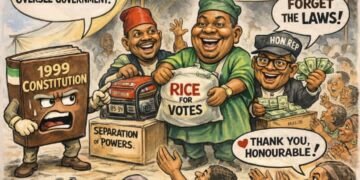

Equally concerning is the perception of unequal enforcement. Ordinary Nigerians are constantly reminded of their civic duty to pay taxes. Yet there is widespread belief that large corporate entities, politically connected individuals, and powerful institutions remain shielded from the full weight of the law. When enforcement appears selective, the moral authority of the state weakens. Citizens begin to ask a simple but dangerous question: why should the weak comply when the strong evade?

This perception is reinforced by developments in the banking sector. Complaints about unexplained charges, delayed reversals, and opaque fee structures remain common. While regulators insist that frameworks for consumer protection exist, the lived experience of many customers suggests enforcement is slow and sanctions insufficiently visible. In a system where banks are seen as profiting quietly from customers while tax authorities intensify pressure on individuals and small businesses, resentment naturally grows.

It is important to be fair. The government is operating under immense fiscal pressure. Infrastructure needs are enormous. Debt servicing consumes a significant share of revenue. Public services require funding. From this perspective, the urgency driving the tax reform is not malicious; it is structural.

Nevertheless, urgency must not override legitimacy. History shows that tax systems imposed without trust do not yield sustainable revenue. They drive evasion, expand the informal economy, and ultimately weaken state capacity. Enforcement-first approaches may deliver short-term gains, but they corrode the long-term social contract.

What, then, is required?

First, clarity. Authorities must publish authoritative, easily accessible explanations of the new tax regime, written in plain language. Citizens should know not only what they owe, but also their rights, appeal mechanisms, and protections against abuse.

Second, coordination. The federal, state, and local governments must urgently harmonise taxing powers and publish a binding framework that ends multiple taxation. Without this, the rhetoric of reform will ring hollow.

Third, equity in enforcement. Government must be seen to pursue large-scale evasion with the same energy directed at small taxpayers. High-profile audits, transparent reporting of recovered sums, and decisive action against corporate avoidance will send a powerful signal that sacrifice is shared.

Fourth, visible returns. Nigerians need to see tangible evidence that taxes collected translate into improved roads, healthcare, education, and security. When citizens can draw a clear line between what they pay and what they receive, compliance becomes rational rather than coerced.

Nigeria stands at a delicate fiscal crossroads. The 2026 tax reform can either mark the beginning of a more stable, accountable revenue system or deepen distrust between the state and its citizens. The difference will be determined not by the text of the law alone, but by how it is implemented.

Tax reform should be a bridge between government and society, not a wedge. To succeed, it must be anchored in transparency, fairness, and empathy for the economic realities Nigerians face. Only then can taxation fulfil its true purpose: sustaining the state without suffocating the people.

Ogundipe,a Former President Nigeria and Africa Union of Journalists writes from Abuja.