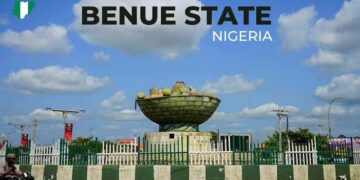

A few weeks ago, I visited Comrade Mashood Erubami at his Old Ife Road, Ibadan office. The visit was not my first to Comrade Erubami, as I had visited him at different times, specifically while I was a news reporter with the Broadcasting Corporation of Oyo State (BCOS) to conduct interviews on many national issues.

On getting to the office, Erubami welcomed me and was so happy to receive me once again to his office. Before now, each time I visited the office, I always wondered why such an international rights activist of Erubami’s status could stay in such an office. Not because the office was that bad, but I was wondering, Comrade Erubami, who I had been hearing his name when I was in Junior Secondary School in Abeokuta, could stay in such an Even for me as a young journalist and now a media consultant, my office presently can boast of many things that I had expected to see in Comrade Erubami’s office.

What I’m trying to bring out from the above description is that a man of Comrade Erubami never deserved such treatment. There are many things I know about Comrade Erubami as a journalist that I will not write here that will not make one happy, at least for now.

On June 12, 2025, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu chose to address members of the National Assembly instead of National Broadcast, which had been the practice before now.

The climax of the speech was at a point. President Bola Ahmed Tinubu rolled out names of those who fought for the actualization of June 12, 1993. Surprisingly, the name of Mashood Erubami was missing from the list.

Who Is Mashood Erubami?

Mashood was born into a poor, polygamous family who could only afford to educate three of their nine children.

Mashood was one of the three. He completed primary and secondary school and was apprenticed to the building trade.

He left to take a job at Barclay’s Bank in 1976. He was rapidly promoted to supervisor and loan officer. While at the bank, he became involved in union activities.

He rose rapidly through the union hierarchy, becoming chairman of the state branch and member of the national negotiating team for the bank worker’s union in 1990.

When Mashood became involved in the Campaign for Democracy in 1991, he resigned from his bank job and union duties. He set up a computer company with two friends. The company works primarily with non-profit organizations and will not accept work from any agency of the Nigerian government.

He leads movement aimed at educating Nigerians in citizenship and, in particular, non-violent solutions to social problems.

This description of Moshood Erubami’s work was prepared when Moshood Erubami was elected to the Ashoka Fellowship in 1996.

Introduction

Mashood Erubami understands that Nigeria’s deeply authoritarian political culture plays itself out everywhere, even in family relationships. The transition to democracy, then, is going to take more than the military abiding by the results of an occasional election. He believes that without the foundations of a civil society in place, there can be no democracy.

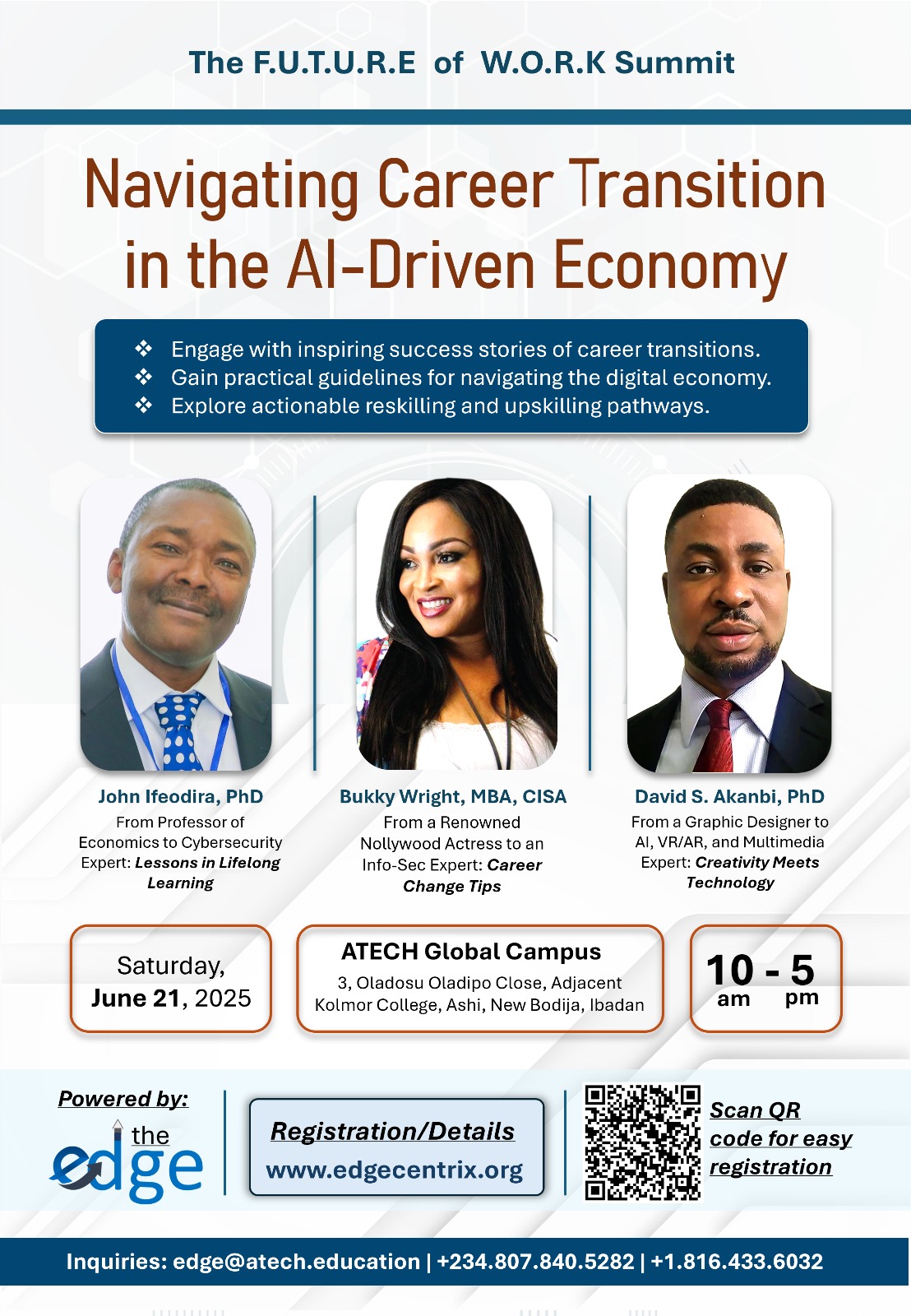

In 1993 a demonstration by half-naked women (in Nigeria a symbol of the highest political disrespect) was met by the government with gunfire that left many women dead.In an effort to better coordinate their work, a broad range of labor unions, human rights groups and others joined forces to establish the Campaign for Democracy in 1991. One of the newest groups that joined this broader coalition was the Social Justice Movement, that brought together under one umbrella the state and national leaders of the Road Transport Workers Union, the National Association of Automobile Technicians, an organization of women, and an association of farmers in Oyo State.

As Vice President of the Social Justice Movement, Mashood realized that if he was going to harness the energies of the Campaign’s member organizations effectively, he would have to undertake education of its members in human rights. Mashood drew up a detailed blueprint for doing this and won board approval for his plan. His first step was to establish the Centre for Human Rights in 1992 in the city of Ibadan in Oyo State. Using Centre volunteers, he began working with the Road Transport Workers’ Union.

Erubami was a vocal critic of military rule and actively participated in protests and demonstrations against the successive military governments that governed Nigeria.

He worked to expose human rights violations committed by the military regimes and advocated for the protection of fundamental freedoms.

Erubami’s activism was rooted in the belief that democracy was the best form of government for Nigeria, and he worked tirelessly to promote democratic values and institutions.

Transition to Democracy:

He played a role in the transition to the Fourth Republic, which began with the death of military dictator General Sani Abacha in 1998 and the subsequent handover to civilian rule in 1999.

In all my interactions with him, one day he will never forget was Ibadan rally tagged “Eyin Alasalatu ki lee waa deebi” which was organised by Gen Abacha’s hachet men in Ibadan, Late Alhaji Lamidi Adedibu, Aare Abdul Azeez Arisekola Alao. That day would have been his last day on earth as many innocent lives were lost on that day.

Erubami led many rallies in and around the South-West. Many of his colleagues’ Comrade were honoured. The likes of Late Beeko Ransome Kuti, Uba Sani, among many others. While I’m not for now blaming President Bola Ahmed Tinubu for this very expensive ommission, it is important for those who are working with the president to correct the anomalies.

My Dear President, sir, please, kindly find any means to correct this ommission.

May God bless the Federal Republic of Nigeria..

Lekan Shobo Shobowale is a journalist and chairman, Nigeria Association of Christian Journalists, Oyo State.